Imagine a cell phone you can fold up and carry in your wallet. When you drop it, nothing cracks or breaks, or if it does, it repairs itself. And when it’s time for an upgrade, the old phone will biodegrade instead of taking up space in a landfill.

Maybe you’d rather wear your laptop or tablet in the fibers of your clothes, or wear a monitor that provides constant data about your health but feels no different than your own skin.

This is the future of electronics, and it’s happening in UC Merced Professor Yue ‘Jessica’ Wang’s lab.

Wang and her students are synthesizing organic polymeric compounds that conduct electricity and behave like no electronics on the market today.

These are conjugated polymers — plastics — that conduct electricity like copper or silicon. However, conducting plastics have a distinct advantage over metals that are mined.

“With mined materials the Earth has created, we are rather restricted with their physical properties. With synthetic polymers, we can infuse virtually any desired electrical, mechanical or optical properties because we get to create them in the lab,” Wang said. “They can be made stretchable, self-healing and biodegradable — properties we don’t commonly associate with electronics. They are becoming the building blocks for all kinds of innovations.”

A materials scientist and engineer, Wang’s vision for what she and her students can do with these synthesized materials earned her a coveted spot as one of 10 finalists for the prestigious and highly competitive Moore Inventor Fellowships this year.

“Jessica's research epitomizes the type of endeavor that UC Merced's growing reputation for excellence is built on: creative ideas, interdisciplinary teamwork, environmental sustainability, and the connection of new fundamental knowledge to practical applications,” said Professor Christopher Viney, founding faculty member and chair of the Materials Science and Engineering Department in the School of Engineering.

The competition is supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation in search of inventors to shape the next 50 years of science and technology, and Wang’s proposal to create bio-inspired, environmentally sustainable electronics stood out from more than 200 innovative entries from all over the country.

Wang, a first-year professor, was up against other finalists who have more seniority and come from institutions such as Stanford, Harvard and Princeton universities and UCLA. Even though her proposal didn’t snatch one of the top awards in the end, Wang said she was honored to represent UC Merced on the national stage.

“Even though our campus is young, being selected as one of the finalists in such a high-level competition shows that we are on the same playing field as some of the most renowned universities in the world. That’s exciting and energizing,” Wang said.

She earned a $25,000 award for being a finalist, which she is putting right back into the lab.

“This is very interdisciplinary work,” Wang said, “and the projects have a lot of components.” That means lots of opportunities for students to be involved.

Her nine undergraduate students, six graduate students and one postdoctoral researcher come from backgrounds in bioengineering, chemistry, mechanical engineering and materials science, and get to work in the areas they want to pursue.

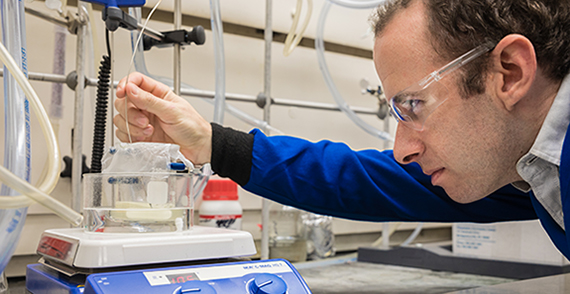

Each team member has his or her own specialty. For example, postdoctoral researcher Rob Jordan, who followed Wang to UC Merced from UCLA, designs and synthesizes materials with programmable physical properties. Ian Hill, a third-year grad student from Riverbank, transforms these materials into a form that can be extruded through a 3D printer to create electronic components of shapes that perfectly resemble the 3D topography of human bodies.

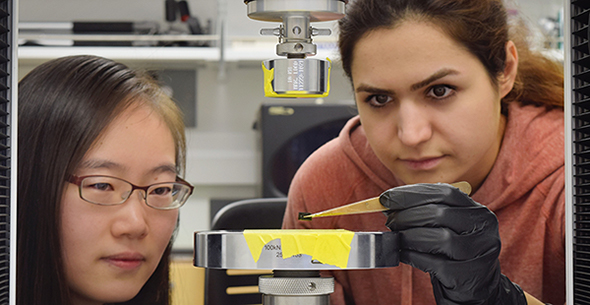

Victor Hernandez, from Los Angeles, a first-year grad student, is responsible for characterizing the materials and figuring out ways to make them more mechanically resilient and electrically conductive. Kiana Shirzad, a second-year grad student from Iran, is combining materials to create properties not observed in either of the original components.

John Misiaszek, a third-year undergrad from Encinitas, designs and builds instruments the team uses to conduct its research, including 3D printing a custom 3D printer that tailors to the processing needs of materials the team developed.

Together, they are all working to better understand the materials and what they can do with them and creating next-generation electronics that exceeds any current imaginations.

“Plastics have revolutionized the world,” Hernandez said, “but they are well-known for their insulating properties. That’s what makes the conductive plastics in our lab so peculiar.”

One aspect that excites researchers like Jordan is the way the materials can fit into a circular economy.

“They let us consider the whole life of a product, because when they are no longer needed, they can be recycled or re-processed and reused, or they will biodegrade without causing any harm in landfills,” he explained.

"All technological progress depends on the availability of the right materials and relevant expertise,” Viney said. “Jessica's lab is at the forefront of providing both.”