As a child, Kevin Dawson traveled from California to visit his grandmother in Harlem, where he recalls playing in Jackie Robinson Park. Dawson, an avid swimmer and surfer, would peer through a fence with his cousins to check out the park’s large swimming pool.

“I remember thinking how fun it’d be to go in the pool. But there was never any water,” he said. “It was a disadvantaged and underfunded community.”

The experience is one that inspired Dawson, a professor of history at UC Merced , to explore the historical relationship African-Americans and their predecessors had with water.

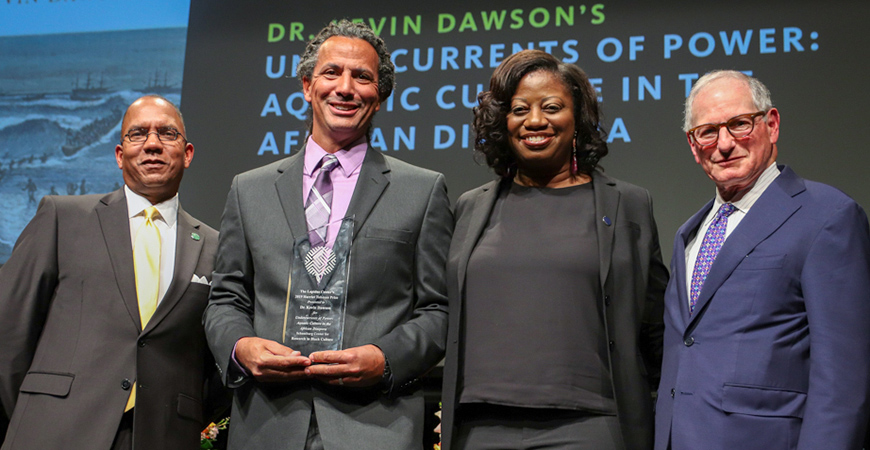

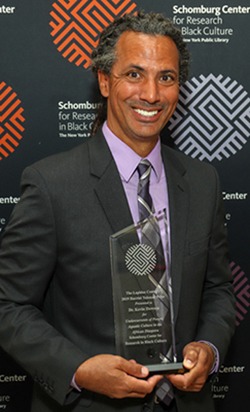

Now, he is honored as the 2019 winner of the Harriet Tubman Prize for his book “Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora” (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018).

The prize is awarded by the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, part of The New York Public Library.

Dawson returned to Harlem to accept the award during an Oct. 10 ceremony.

“It’s a huge honor, and it’s also really humbling, to receive this prize named for a woman who had this indomitable spirit, who was a champion of freedom,” Dawson said.

The award recognizes the best U.S.-published, nonfiction book on the slave trade, slavery and anti-slavery in the Atlantic World.

The award’s jury of prominent historians wrote, “Dawson’s generative work opens up new ways of studying Atlantic History and the African Diaspora.”

Dawson’s book reveals how West Africans enslaved in the Americas carried with them a rich body of aquatic traditions such as swimming, diving and sailing.

He upends popular beliefs, such as the origin of watercraft used in the American South. Evidence suggests, he said, that enslaved Africans used techniques from West Africa, not indigenous Americans, to build canoes.

As for surfing, he notes, the earliest written descriptions of the sport came from Ghana in the 1660s — a century before English explorers witnessed it in Hawaii.

Yet, even in the classic surf movie “Endless Summer,” Dawson said, the American travelers boast of introducing the sport to a Ghananian beach while people can be seen surfing in the background.

“There has been an erasure of history,” Dawson said. “It is part of a mythology that Africa had nothing of value and merit for the rest of the world. … The argument was that Africa was this backwards, uncivilized, savage place and that the only things Africans had to offer was their labor.”

For centuries, West Africans recognized waterways as cultural and social spaces, not fearsome intervals between land. European explorers who came upon them marveled at their abilities in an oceanscape considered to be the “realm of Satan.”

In the New World, waterways became places for commerce and recreation. Dawson’s book tells of enslaved women who steered canoes to market and of men who parlayed their diving expertise, say, to salvage gold or silver from a shipwreck, to secure privileges such as time off.

With the end of slavery, however, white merchants and land owners could no longer profit from the aquatic skills of slaves.

“Once freed, they begin to be forced off the water into more strenuous, less profitable work,” Dawson said.

Over time, as waterfronts became desirable recreational and residential areas for white Americans, blacks increasingly lost access to beaches and lakes — a trend that continues. For both whites and blacks, swimming and boating came to be seen as “un-black activities.”

There has been an erasure of history. It is part of a mythology that Africa had nothing of value and merit for the rest of the world.

The USA Swimming Foundation reports that two-thirds of African-American children have little to no ability to swim, far worse than rates for others. The widespread lack of water skills has dire results. Black children and teens are 5.5 times more likely to drown in swimming pools, according to the Centers for Disease Control .

Dawson’s research is being cited by swimming advocates and community organizers to push for greater access to pools and aquatic lessons among urban youth. “Undercurrents of Power,” he said, is helping challenge the myth that “black people don’t swim.”

For Dawson, it’s a mythology that gave him his first taste of racism when he was about 5 years old.

“I was playing with some white kids at Cabrillo Beach, by Long Beach, and I said, ‘Hey, let’s go swimming!’ One of the kids said, ‘Colored people don’t swim.’

“I had no idea what that even meant, but I knew it was an insult.”

Dawson challenged the older, larger boy to a race — in the water — and easily won.

“He wanted to fight me and I was able to keep toying with him, letting him get kind of close to me and then swimming off and laughing.”

The encounter led Dawson to recognize that power relationships built on land do not necessarily extend to the water.

“The kid probably could’ve beaten me up on land,” he said. “But in the water, he was powerless.”